Audible Data Transmission: When Humans Become the Codec

Audible Data Transmission: When Humans Become the Codec

How a 2016 experiment in encoding binary data as song revealed principles we're only now rediscovering in AI development

When I created a system for encoding digital information as singable chant in 2016, I wasn't thinking about neural codecs, compression algorithms, or the information-theoretic properties of human memory. I was solving a simple problem: how do you transmit binary data when all you have is a human voice and someone willing to listen?

The answer turned out to be more interesting than the question.

The Problem Space

Modern AI development has trained us to think about encoding in specific ways. We optimize for GPU throughput, minimize latency, maximize compression ratios. We assume machines at both ends of the channel and design accordingly. But what happens when the channel is the machine? When the codec has to run on wetware instead of hardware?

This isn't a hypothetical question. It's one that's been answered repeatedly throughout history—in Russian prison camps, in monastic traditions, in oral cultures that preserved complex knowledge without writing. But it's also deeply relevant to how we think about AI systems today, particularly as we build models that need to interface with human cognition rather than just process data.

The Encoding Chain

The system I developed follows a simple pipeline that any developer will recognize:

binary → Morse code → phonetic syllables → rhythmic chant

Each layer is strictly reversible. No information is lost. No semantic drift occurs. This isn't a mnemonic device or a poetic encoding—it's a proper codec with defined rules for both encoding and decoding.

The core mapping is minimal:

- Dot (·) → "ти" (ti)

- Dash (–) → "та" (ta)

- Letter boundary → pause

- Word boundary → extended pause

That's it. Everything else emerges from this foundation.

Why This Matters for AI Development

We're currently witnessing an explosion of interest in multimodal models, audio codecs, and systems that bridge the gap between machine and human understanding. What this encoding system demonstrates—and what I didn't fully appreciate in 2016—is that human cognition has specific affordances that differ fundamentally from digital computation.

Humans are terrible at random access. We're bad at precise bit-level manipulation. We struggle with arbitrary symbol sequences. But we're exceptionally good at rhythm, pattern recognition, and detecting deviation from expected structures. The encoding leverages these strengths rather than fighting them.

Consider how this compares to modern neural audio codecs like EnCodec or SoundStream. Those systems learn to compress audio by discovering latent representations that preserve perceptual quality. The audible data transmission system does something similar, but the "latent representation" is explicitly designed for the perceptual and cognitive capabilities of human memory.

Song as Error Correction

One of the more surprising properties of this system emerged when I started teaching it to others. When someone made a mistake while chanting the encoded message, it sounded wrong. The rhythmic expectation created by proper encoding made errors perceptually salient without any additional mechanism.

This is essentially an organic error-detecting code. The meter and rhythm function like implicit parity checks—deviations from the expected pattern are immediately obvious to trained listeners. No CRC calculation required, just pattern recognition that humans do naturally.

In information-theoretic terms, song introduces redundancy without adding data. The temporal structure provides a scaffold that makes the encoded information more robust against noise (memory decay, distraction, ambient sound) while remaining fully reversible.

The Historical Context

When I first developed this system, I had a vague sense that similar approaches must have existed before. The research confirmed this, but with an important distinction: previous systems were emergent and ad hoc. Russian prisoners used rhythmic tapping and chanting to communicate between cells, but there was no standardized phonetic layer. Monastic traditions encoded text in melodic form, but not at the binary level. Talking drums transmitted linguistic information, but not arbitrary data.

What makes this system novel isn't that it uses rhythm or vocalization—those are ancient. What's novel is the explicit formalization of the encoding chain and the recognition that humans can serve as literal codecs for binary information when the encoding is designed with human cognition in mind.

This connects directly to current work in human-AI interaction. We spend enormous effort trying to make models that can "understand" human input, but we rarely ask the inverse question: how should we structure information so that humans can process it with the same reliability as machines?

Practical Implications

The immediate use cases for audible data transmission are obviously limited. You're not going to replace fiber optics with singing. But the underlying principles have broader applications:

Education: This system makes the abstraction layers of encoding visible and tangible. Students can literally hear the transformation from binary to signal and back. It's a teaching tool that makes information theory concrete.

Human-computer interaction: When we design systems that need to convey state or status to humans, we typically use visual indicators or synthesized speech. But what if the information itself was structured to be cognitively efficient? What would a system status update sound like if it was designed to be memorized and repeated accurately rather than just understood?

AI model design: The success of this encoding system depends on aligning the representation with the processor's capabilities. This is exactly what we do when we design attention mechanisms, positional encodings, or embedding spaces for neural networks. The difference is that here the "processor" is a human brain, which forces us to think explicitly about cognitive affordances.

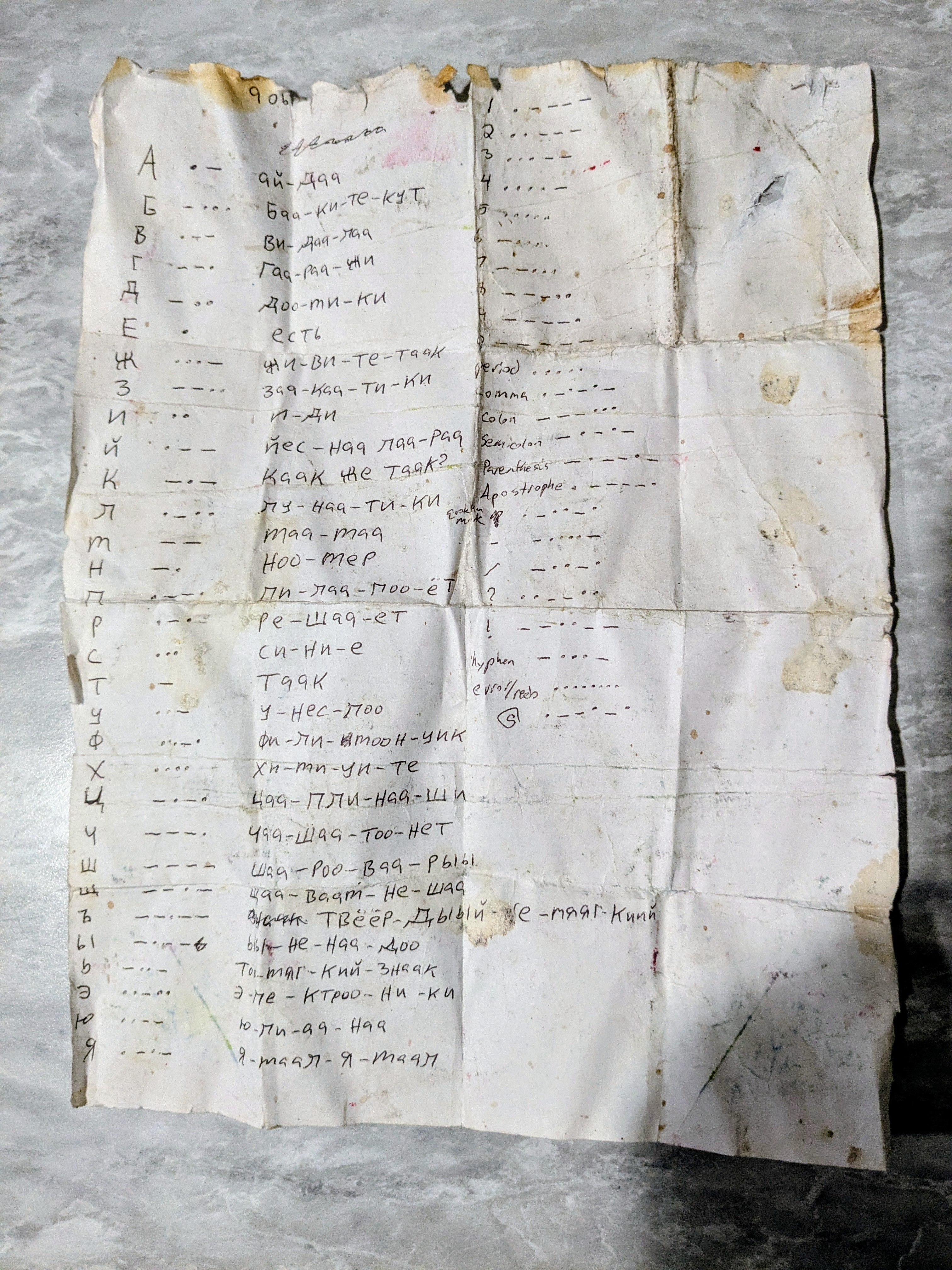

Looking at the Artifact

The image I've included shows the original 2016 encoding chart—handwritten Cyrillic characters mapped to Morse patterns and phonetic representations. It's weathered, folded, clearly used. This wasn't theoretical work; it was a practical tool.

Each row maps a Cyrillic letter to its Morse equivalent and then to the phonetic sequence. The right side shows numbered patterns, likely example messages or teaching sequences. The physical artifact matters because it demonstrates something important: this encoding was designed to be memorized and internalized, not looked up. The chart is training material, not a reference manual.

This is fundamentally different from how we typically think about encoding schemes in software development. A lookup table is perfectly fine when you have random access memory. But when the "memory" is biological, the encoding needs to be learnable, not just correct.

Connecting to Current Work

As I've shifted more deeply into AI development, I keep returning to this 2016 project because it illustrates principles that are increasingly relevant. We're building systems that need to be interpretable, that need to interface with human cognition, that need to compress information in ways that preserve what matters while discarding what doesn't.

The audible transmission system is a codec optimized for a specific, constrained processor: human memory and vocalization. It succeeds not by fighting the limitations of that processor but by embracing them. This is exactly the approach we need when designing AI systems that humans will actually use, understand, and trust.

Every encoding makes tradeoffs. Video codecs discard information the human eye won't notice. Audio codecs preserve perceptual quality at the expense of waveform fidelity. This system discards throughput and storage efficiency to maximize memorability and error detection. The tradeoffs are different because the constraints are different, but the underlying challenge is identical: how do you represent information in a way that's optimized for the system that will process it?

The Broader Question

Building this encoding system taught me something that's become increasingly central to my work: information is substrate-independent, but representation is not. The same data can be encoded countless ways, and the choice of encoding determines what you can efficiently do with that data.

When we build AI models, we're making encoding decisions constantly—how we tokenize text, how we represent images, how we structure prompts. These decisions matter enormously, but we often make them based on computational convenience rather than considering what representation would actually be optimal for the task.

The audible transmission system forced me to think about encoding from first principles because I couldn't fall back on established conventions. There was no library to import, no standard format to adopt. The result was something that looks strange from a traditional software perspective but makes perfect sense when you understand the constraints it was designed for.

Where This Goes Next

I'm not actively developing the audible transmission system—it was never meant to be production software. But the insights it generated continue to inform how I think about AI development, particularly around interpretability and human-AI collaboration.

If you're working on systems that need to interface with human understanding, I'd encourage you to think about what an "encoding for cognition" would look like in your domain. Not a visualization or an explanation, but an actual representation designed to be processed by human wetware with the same precision we expect from silicon.

The results might surprise you, just as they surprised me when I heard someone successfully decode a message they'd memorized as a chant without ever seeing the written form.

The encoding chart shown here is from my original 2016 development work. The system is documented in a technical paper I wrote analyzing it as a formal encoding layer rather than a curiosity. If you're interested in the full information-theoretic treatment, I'm happy to share it.

For those wondering: yes, I can still decode messages in this format. Yes, it still sounds wrong when someone makes a mistake. And yes, I absolutely think there are lessons here for how we build the next generation of AI systems.

The encoding chart shown here is from my original 2016 development work. The system is documented in a technical paper I wrote analyzing it as a formal encoding layer rather than a curiosity. If you're interested in the full information-theoretic treatment, I'm happy to share it below.

Information-Theoretic Analysis of Audible Binary Transmission via Rhythmic Vocalization.pdf